I am pleased to welcome Mercedes Rochelle back to my blog to share an article about the Percy family and the Battle of Shrewsbury as part of the blog tour for her novels The Usurper King and The Accursed King. I want to thank Mercedes Rochelle and The Coffee Pot Book Club for allowing me to be part of this blog tour.

I am pleased to welcome Mercedes Rochelle back to my blog to share an article about the Percy family and the Battle of Shrewsbury as part of the blog tour for her novels The Usurper King and The Accursed King. I want to thank Mercedes Rochelle and The Coffee Pot Book Club for allowing me to be part of this blog tour.

The Percies were such a powerful force in the North they practically acted like rulers in their own kingdom. For much of Richard II’s reign and the beginning of Henry IV’s, Earl Henry Percy and his son, Sir Henry (nicknamed Hotspur) alternated between the wardenships of the East Marches and the West Marches toward Scotland. They were experienced in dealing with the tempestuous Scots, and their retainers were fiercely loyal. When Henry IV returned from exile and began his campaign that led to the throne, the Percies were his staunchest supporters; they provided a large portion of his army. Henry Percy was directly responsible for persuading King Richard to turn himself over to Henry Bolingbroke—the beginning of the end of Richard’s fall.

Caption: Froissart Chronicles by Virgil Master, Source: Wikimedia

Caption: Froissart Chronicles by Virgil Master, Source: Wikimedia

Naturally, this was not done out of sheer kindness. Henry Percy expected to be amply rewarded for his services, and at the beginning he was. But the king was uncomfortable about the potential threat of this overweening earl. He soon began to promote his brother-in-law, Ralph Neville the Earl of Westmorland as a counterbalance, chipping away at Percy’s holdings and jurisdictions. Additionally, the Percies felt that they were not being reimbursed properly for their expenses; by 1403 they claimed that the king owed them £20,000—over £12,000,000 in today’s money. But even with all this going on, it’s likely that the earl may have contained his discontent, except for the belligerence of his impetuous son.

One possible catalyst was Hotspur’s refusal to turn over his hostages taken at the Battle of Homildon Hill. This battle was a huge win for the Percies in 1402, where so many leaders were taken—including the Earl of Douglas—that it left a political vacuum in Scotland for many years to come. Once he learned of this windfall, King Henry insisted that the Percies turn over their hostages to the crown. It was his right as king—even if it was against the code of chivalry— though his highhanded demand was probably not the wisest choice, considering the circumstances. There were many possible reasons he did so. He was desperately short of funds—as usual. It’s possible he may have wanted to retain the prisoners as a means of ensuring Scottish submission. Earl Henry agreed to turn over his hostages, but Hotspur absolutely refused to surrender Archibald Douglas, letting his father take the king’s abuse. One can only imagine that all was not well in the Percy household, either.

There was more at stake. The king had just returned from a humiliating fiasco in Wales, where he had campaigned in response to the English defeat at Pilleth, where Edmund Mortimer was captured by the Welsh. Mortimer was the uncle of the eleven-year-old Earl of March, considered by many the heir-presumptive to the throne (and in Henry’s custody). Edmund was also the brother of Hotspur’s wife. By the time Henry demanded the Scottish hostages, it was commonly believed that the king had no intention of ransoming Mortimer; after all, he was safely out of the way and couldn’t champion his nephew’s cause. This rankled with Hotspur, and it is possible that he thought to use Douglas’s ransom money to pay for Mortimer’s release himself.

Hotspur finally rode to London in response to the king’s demands, but he went without Douglas. Needless to say, this immediately provoked an argument. When Hotspur insisted that he should be able to ransom his brother-in-law, Henry refused, saying he did not want money going out of the country to help his enemies. Hotspur rebutted with, “Shall a man expose himself to danger for your sake and you refuse to help him in his captivity?” Henry replied that Mortimer was a traitor and willingly yielded himself to the Welsh. “And you are a traitor!” the king retorted, apparently in reference to an earlier occasion when Hotspur chose to negotiate with Owain Glyndwr rather than arrest him. Allegedly the king struck Percy on the cheek and drew his dagger. Of course, attacking the king was treason and Hotspur withdrew, shouting “Not here, but in the field!” All of this may be apocryphal, but it is certainly powerful stuff.

The whole question of Mortimer’s ransom became moot when he decided to marry the daughter of Glyndwr and openly declare his change of loyalties on 13 December 1402. No one knows whether Hotspur’s tempestuous interview with King Henry happened before or after this event; regardless, a bare minimum of eight months passed before Shrewsbury. Were they planning a revolt all this time? It is likely that early in 1403 one or both of the Percies were in communication with the Welsh. Owain Glyndwr was approaching the apex of his power, and a possible alliance between him, Mortimer, and the Percies could well have been brewing. It would come to fruition later on as the infamous Tripartite Indenture (splitting England’s rule between them), but by then Hotspur was long dead.

Caption: BnF MS Franc 81 fol. 283R Henry IV and Thomas Percy at Shrewsbury from Jean de Wavrin- Creative commons license

Caption: BnF MS Franc 81 fol. 283R Henry IV and Thomas Percy at Shrewsbury from Jean de Wavrin- Creative commons license

No one has been able to satisfactorily explain just why the Percies revolted against Henry IV. Most of the evidence points to their self-aggrandizement. And looking at the three years following his coronation, it became evident that King Henry was not willing to serve as their puppet, nor was he willing to enhance their power at the expense of the crown. The Percies’ ambitions were thwarted by the king’s perceived ingratitude, and the consensus of modern historians is that they hoped to replace him with someone more easily manipulated.

There was one more Percy involved in all this: Thomas, younger brother of Earl Henry and uncle to Hotspur. He was probably the most able—if the least flamboyant—member of the Percy clan in this period. From soldier to commander, Admiral of England to Ambassador, Captain of Calais, Justiciary of South Wales, he made it all the way to Steward of the Royal Household. And that wasn’t all. He was also Earl of Worcester, which almost made him an equal to his brother, the great Earl of Northumberland.

His involvement in the Shrewsbury uprising was puzzling. He had much to lose and nothing to gain. Shakespeare notwithstanding, I don’t really think Thomas was the motivating force behind the rebellion that led to the Battle of Shrewsbury. It’s true that his fortunes were waning; the king had recently replaced him as Lieutenant of Wales with the sixteen-year-old Prince Henry. Whether the Percies won or lost the battle, there’s a better-than-even chance that he would rise and fall along with them, whether he participated in the rebellion or not. Was that enough to push him over the edge? I suspect that his affection for Hotspur had a lot to do with it, and in the end, it’s likely he couldn’t conceive of fighting against his own kin. Poor Thomas lost his head the day after the battle, paying a high price for his loyalty.

THE USURPER KING by Mercedes Rochelle

THE USURPER KING by Mercedes Rochelle

Book 4 of The Plantagenet Legacy

Blurb:

From Outlaw to Usurper, Henry Bolingbroke fought one rebellion after another. First, he led his own uprising. Then he captured a forsaken king. Henry had no intention of taking the crown for himself; it was given to him by popular acclaim. Alas, it didn’t take long to realize that having the kingship was much less rewarding than striving for it. Only three months after his coronation, Henry IV had to face a rebellion led by Richard’s disgruntled favorites. Repressive measures led to more discontent. His own supporters turned against him, demanding more than he could give. The haughty Percies precipitated the Battle of Shrewsbury which nearly cost him the throne—and his life.

To make matters worse, even after Richard II’s funeral, the deposed monarch was rumored to be in Scotland, planning his return. The king just wouldn’t stay down and malcontents wanted him back.

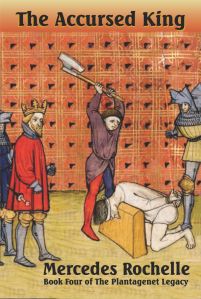

THE ACCURSED KING by Mercedes Rochelle

THE ACCURSED KING by Mercedes Rochelle

Blurb:

What happens when a king loses his prowess?

The day Henry IV could finally declare he had vanquished his enemies, he threw it all away with an infamous deed. No English king had executed an archbishop before. And divine judgment was quick to follow. Many thought he was struck with leprosy—God’s greatest punishment for sinners. From that point on, Henry’s health was cursed and he fought doggedly on as his body continued to betray him—reducing this once great warrior to an invalid.

Fortunately for England, his heir was ready and eager to take over. But Henry wasn’t willing to relinquish what he had worked so hard to preserve. No one was going to take away his royal prerogative—not even Prince Hal. But Henry didn’t count on Hal’s dauntless nature, which threatened to tear the royal family apart.

Buy Links:

Universal Buy Links:

The Usurper King: https://books2read.com/u/3nkRJ9

The Accursed King: https://books2read.com/u/b5KpnG

The Plantagenet Legacy Series Links:

All titles in the series are available to read on #KindleUnlimited.

Author Bio:

Author Bio:

Mercedes Rochelle is an ardent lover of medieval history and has channeled this interest into fiction writing. She believes that good Historical Fiction, or Faction as it’s coming to be known, is an excellent way to introduce the subject to curious readers.

Her first four books cover eleventh-century Britain and events surrounding the Norman Conquest of England. Her new project is called “The Plantagenet Legacy” taking us through the reigns of the last true Plantagenet King, Richard II, and his successors, Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI. She also writes a blog: HistoricalBritainBlog.com to explore the history behind the story.

Born in St. Louis, MO, she received by BA in Literature at the University of Missouri St.Louis in 1979 then moved to New York in 1982 while in her mid-20s to “see the world”. The search hasn’t ended!

Today she lives in Sergeantsville, NJ with her husband in a log home they had built themselves.

Author Links:

Website: https://mercedesrochelle.com/

Twitter: https://x.com/authorrochelle

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mercedesrochelle.net

Book Bub: https://www.bookbub.com/authors/mercedes-rochelle

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Mercedes-Rochelle/author/B001KMG5P6

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1696491.Mercedes_Rochelle

Also known as Richard Plantagenet.

Also known as Richard Plantagenet.  (Born September 16, 1387- Died August 31, 1422).

(Born September 16, 1387- Died August 31, 1422).  Lancaster.

Lancaster.  (Born January 6, 1367- Died on or about February 14, 1400).

(Born January 6, 1367- Died on or about February 14, 1400).