I am pleased to welcome Sam Mee, founder of the Antique Ring Boutique, to my blog today to share an article about Tudor jewelry.

Jewelry was predominantly religious in the austere Middle Ages, focusing on relics, devotional rings, and crosses. But the Tudor rulers developed it as a way to project their own royal power and authority. Clothing fashions of the time emphasized structure, and monarchs like Henry VIII and Elizabeth I integrated jewelry to proclaim their status and divine favor.

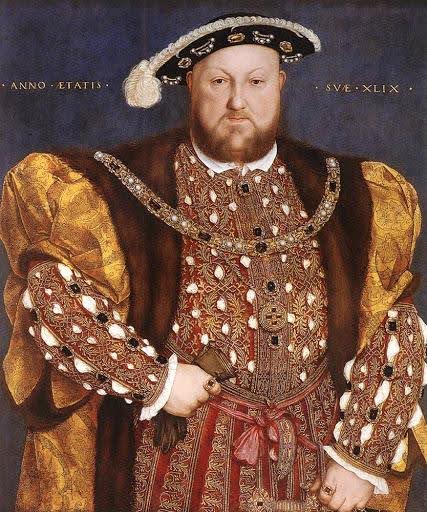

This was the age of portraiture, when the elite commissioned likenesses as propaganda. Hans Holbein the Younger depicted Henry VIII in a way that showed off his jewels and chains of office as much as his formidable bulk (and codpiece). Holbein’s most famous image of Henry is a 1537 mural that, while destroyed by fire in 1698, is still known through copies. It shows the King with a powerful stance and wearing multiple chains and rings to further emphasized his authority and wealth.

Holbein portrait, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1024px-After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Holbein portrait, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/1024px-After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Three similar Armada portraits of Elizabeth I were painted after England defeated the Spanish Armada. They take allegory even further. The Queen is almost encased in pearls. Her gown is embroidered with them, they sit on her hair, and pearl ropes hang from her neck, all to symbolize chastity and divine protection. More explicitly, her hand rests on the globe as a symbol of empire. Her powerful warships are visible in the background behind her gem-encrusted crown, signifying divine authority.

Armada portrait, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7b/Elizabeth_I_%28Armada_Portrait%29.jpg

Armada portrait, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7b/Elizabeth_I_%28Armada_Portrait%29.jpg

In fact, Elizabeth I was rarely painted without pearls – other examples include the Darnley Portrait (c1575) and Rainbow Portrait (c1600). The pearls repeatedly symbolized the Virgin Queen’s chastity and wealth in bodily form.

The sumptuary laws

If gems and clothing signified power, then rulers needed to control who wore what. Medieval 15th-century sumptuary laws started to codify this across Europe. A 1463 English statute restricted who could wear “royal purple”, while a 1483 act restricted velvet to knights and lords and satin for gentry with a yearly income of £40.

Tudor England was an intensely hierarchical society, and so the laws were tightened further. Elizabeth’s 1574 Act of Apparel spelled out in detail who could wear what – her rules set which fabrics hats could be made of and dictated the length of swords, depending on the wearer’s standing. Check out the list here: https://midtudormanor.wordpress.com/sumptuary-laws/

Jewelry was also regulated with gold chains, heavy pearls, and precious stones reserved exclusively for the nobility.

Enforcement was patchy but real, with surviving court records showing individuals tried for breaches and fined. These laws were somewhat symbolic, though. They were a way to make hierarchy visible rather than consistently enforced. Ambitious merchants and courtiers often flaunted jewels beyond their rank, with monarchs turning a blind eye.

Fashion at court

Jewelry was inseparable from clothing at court. Goldsmiths worked hand in hand with tailors, and jewels were sewn directly into doublets and headdresses.

We know Henry VIII wore vast gold chains and pendants and even occasionally jeweled codpieces. Courtiers followed suit with jeweled hat badges, enameled rings, and ornate girdle books (these were tiny, jeweled prayer books that hung from belts). They also wore gold pearl earrings. Women sported pearls, rubies, and diamonds on top of layered dresses made from richly embroidered fabrics.

Anne Boleyn’s necklace – a large gold “B” with three drop-pearls dangling from it – is one of the period’s most famous jewels. It’s a very personal bit of jewelry that symbolized her individuality and status. (It survives only in portraits – its whereabouts after her 1536 beheading is not known).

Anne Boleyn’s B necklace, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Anne_boleyn.jpg

Anne Boleyn’s B necklace, public domain image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Anne_boleyn.jpg

Global trends and treasures

The rise in the prominence of jewelry was part of a wider trend of expanding horizons – culturally, societally, geographically, and economically. Spain’s influx of New World gold and silver boosted Europe’s wealth, with England claiming its own share through figures like Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake.

There’s extraordinary archaeological evidence of this, not just from the images of the time but from the Cheapside Hoard, discovered in 1912 beneath a London cellar. It’s a collection of more than 400 pieces. There are emerald rings, diamond pendants, and enameled chains with gems sourced from Colombia, India, Burma, and Brazil. The treasure shows that London goldsmiths had access to a global supply of jewels long before the height of the empire.

Together with portraits, the Hoard is the richest record we have of Tudor jewelry, showing how jewels were actually made. You can read more about it here: https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/london-stories/jewels-cheapside-hoard/

Evolution of Tudor Jewelry

New fashions, new materials, and new freedoms (for some). Tudor jewelers developed new techniques to match these wider changes in society, combining medieval traditions with Renaissance artistry. Enameling reached new heights, and these techniques were carried forward into Georgian mourning jewelry and even into Victorian revival pieces.

Foil-backing was widely used in Tudor times to enhance jewels. Thin sheets of colored foil were placed behind gems like diamonds, rubies, or rock crystal to enhance their brilliance. This technique remained common until the 18th century, when more advanced diamond cutting began to produce inherent sparkle.

Gem cutting itself advanced in the Tudor period. Gemstones are rarely cut in bespoke shapes but tend to use standardized cuts designed to maximize brilliance or colour. This has been true since the Renaissance. Earlier medieval gems were typically worn as cabochons (smooth, polished domes), which enhanced colour but not brilliance. Then, from the late 15th century, jewelry began to experiment with faceting, where flat surfaces were cut at angles to reflect light, and Tudor lapidary work played a key role in the development and take-up of new techniques:

- Cabochon: The oldest approach. A smooth, rounded dome without facets. Used in the medieval period for sapphires, garnets, and emeralds.

- Point cut: This simple cut shaped a diamond into a pyramid with four sides. Mostly common in the 15th century.

- Table cut: Developed in the late 15th century, this removed the top of the pyramid to create a flat “table” facet. It meant increased brilliance and became standard in Tudor jewelry.

- Rose cut: Emerged in the 16th century as diamond saws and polishing technology improved. This had a flat base and a domed top covered in triangular facets to resemble a rosebud. The rose cut was popular until the 19th century.

- Old mine cut: An 18th-century development. It’s a squarish cut combined with a high crown, deep pavilion, and large culet. It was the forerunner of the modern brilliant cut.

You can read more about the evolution from medieval jewelry techniques here. (https://historicalbritainblog.com/the-debt-antique-jewellery-owes-to-the-middle-ages-guest-post-by-samuel-mee/)

Settings in Tudor times typically enclosed the stone with gold, but Tudor jewelers began experimenting with more open settings to admit light. It was the Stuart era that really saw the development of the claw setting for diamonds, where the gem was held with tiny metal arms to allow much more light to pass through, dramatically increasing sparkle.

Tudor trends can be seen in subsequent centuries:

- Georgian jewelers turned enamel and foil into sentimental jewelry such as portrait miniatures (also common in Tudor times) and mourning rings.

- Victorian designers enjoyed historical revival, and they often deliberately echoed Tudor styles, such as heavy Holbein-like gold chains and memento mori skulls.

- Edwardian jewelers drove a revival of Elizabethan-style pears and combined them with lace-like platinum settings.

- Art Deco designs were modernist in geometry but had a strong revivalist theme from Egyptian motifs to statement designs that matched 16th-century theatricality.

Surviving themes

Tudor jeweler was many things: regulated, global, technical, and symbolic. It was constrained by law, used as propaganda, and yet pushed at boundaries. It was part of the evolution of techniques and materials that developed over several hundred years as jeweler changed to become ever more personal. And even specific gem traditions persisted. The Tudor love of pearls was echoed in the Edwardian era. Tudor foiling foreshadowed Georgian brilliance. Tudor enameling was revived multiple times in the centuries that followed. Let’s just hope the codpiece doesn’t return.

About the Author

Sam Mee is the founder of the Antique Ring Boutique (https://www.antiqueringboutique.com/), which sells rings from the Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, and Art Deco eras. He has several guides on his website for buying rings from different historical periods. EG, you can learn more about ring cuts and foiling in the guide to Georgian rings: https://www.antiqueringboutique.com/en-us/pages/georgian. He is a member of both Lapada (https://lapada.org/dealers/antique-ring-boutique/) and BADA (https://www.bada.org/dealer/antique-ring-boutique).

Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet

Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet  The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh

The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh Acts of Apparel

Acts of Apparel  Too much crimson dye?

Too much crimson dye?

Toni Mount Biography

Toni Mount Biography