The Plantagenets, a dynasty that ruled England for over three hundred years. At least that is if you include the Lancastrian and Yorkist kings. Otherwise, the reign of the Plantagenets ended with Richard II being overthrown. So, how did the Plantagenets fall? How did wars, favoritism, and the plague factor into the fall? Helen Carr examines these questions and the rule of three kings over the fourteenth century in her latest book, “Sceptred Isle: A New History of the Fourteenth Century.”

The Plantagenets, a dynasty that ruled England for over three hundred years. At least that is if you include the Lancastrian and Yorkist kings. Otherwise, the reign of the Plantagenets ended with Richard II being overthrown. So, how did the Plantagenets fall? How did wars, favoritism, and the plague factor into the fall? Helen Carr examines these questions and the rule of three kings over the fourteenth century in her latest book, “Sceptred Isle: A New History of the Fourteenth Century.”

I have really enjoyed Helen Carr’s insight into medieval English history in her book, The Red Prince, so when I heard she was writing a book about the Plantagenets again, with a focus on the fourteenth century, I was excited to read it. The idea in this book that caught my attention was the idea that the Plantagenet dynasty ended when Henry of Bolingbroke overthrew Richard II. As someone who believes that the Plantagenet dynasty ended with the death of Richard III, the concept that it ended almost a century earlier is intriguing.

We begin our adventure with a double reburial of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, the idea of King Edward I and his wife Eleanor of Castile. It was a kind gesture, but the prophecy that was left behind would be almost prophetic. With the death of King Edward I, the Hammer of the Scots, the throne passed to his son Edward II. While Edward I was a strong warrior, Edward II was a handsome prince who only cared about his favorites, Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. It would cause those around him, including his wife, Isabella of France, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, to take action against him. Isabella and Mortimer placed Edward III on the throne, but they would soon learn that Edward III was not as passive as his father.

Edward III would return to the warrior state of mind like his grandfather Edward I. With his wife Philippa of Hainault, they would have a large family with many sons, including John of Gaunt and Edward the Black Prince. It would be Edward III who would try to take the French throne for England in a conflict known as the Hundred Years’ War (not the quickest war, and it didn’t go the way Edward III envisioned it). And to top it all off, Edward III had to deal with the emergence of the Black Death and how it affected not only his own family but England and Europe as a whole.

Before Edward III died, his heir, the Black Prince, died, which meant that the Black Prince’s son, Richard II, was destined to be the next king. However, youth and favoritism failed the king as chaos reigned ever since the start of his reign, with the Peasants’ Revolt, and ended with Henry of Bolingbroke becoming the first Lancastrian King, Henry IV.

This was another wonderful book by Helen Carr. It demonstrates Carr’s ability to balance extensive research with a narrative format to create an accessible history book that novices and experts will equally enjoy. My only qualm with this book, if you can call it an issue, is that I wanted it a bit longer so we get more analysis of how this one century affected English and European history as a whole. If you want a book that dives into the history of one of England’s most tumultuous centuries, I highly recommend you read “Sceptred Isle: A New History of the Fourteenth Century” by Helen Carr.

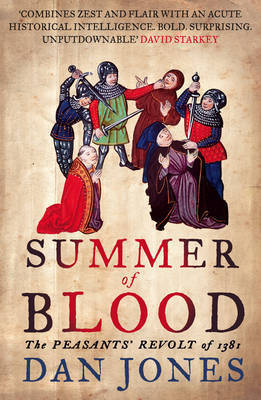

The year was 1381, and England was engulfed in chaos. A band of ruffians and revolters descended on London to achieve political change and a fair chance for the lower classes who suffered greatly from war and plague. The young King Richard II watched as men like Wat Tyler and the preacher John Ball led this ragtag army to his doorstep, fighting against his advisors, like John of Gaunt, to end a poll tax that was their last straw. Why did this ragtag army march on London? How did men like Ball and Tyler convince the masses to march against their sovereign and his government? How did this revolt end, and did the people get what they wanted due to their revolution? Dan Jones brings the bloody story of the first significant revolution by the English people to life in his book, “Summer of Blood: The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.”

The year was 1381, and England was engulfed in chaos. A band of ruffians and revolters descended on London to achieve political change and a fair chance for the lower classes who suffered greatly from war and plague. The young King Richard II watched as men like Wat Tyler and the preacher John Ball led this ragtag army to his doorstep, fighting against his advisors, like John of Gaunt, to end a poll tax that was their last straw. Why did this ragtag army march on London? How did men like Ball and Tyler convince the masses to march against their sovereign and his government? How did this revolt end, and did the people get what they wanted due to their revolution? Dan Jones brings the bloody story of the first significant revolution by the English people to life in his book, “Summer of Blood: The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.” In human history, when citizens have disagreed with a new law or those in charge, they often stage a protest to show their frustration. When their voices are not heard, people often turn to rebellions and revolts to make sure their opinions matter. We might think that revolution and rebellion as a form of protest are modern ideas, but they go back for centuries. Revolutions and rebellions shaped history, no more so than in the middle ages. In his latest book, “Rebellion in the Middle Ages: Fight Against the Crown,” Matthew Lewis examines the origins of the most famous rebellions in medieval England and how they transformed the course of history.

In human history, when citizens have disagreed with a new law or those in charge, they often stage a protest to show their frustration. When their voices are not heard, people often turn to rebellions and revolts to make sure their opinions matter. We might think that revolution and rebellion as a form of protest are modern ideas, but they go back for centuries. Revolutions and rebellions shaped history, no more so than in the middle ages. In his latest book, “Rebellion in the Middle Ages: Fight Against the Crown,” Matthew Lewis examines the origins of the most famous rebellions in medieval England and how they transformed the course of history.