I am pleased to welcome Toni Mount to share her advice about Tudor men’s fashion to promote her latest book, How to Survive in Tudor England. I would like to thank Toni Mount and Pen and Sword Books for allowing me to be part of this blog tour.

In writing my new book How to Survive in Tudor England I realised how tricky it was to be fashionable during the sixteenth century: hard work and expensive for men and women. So here’s a taster of what was required for a man to get noticed at court.

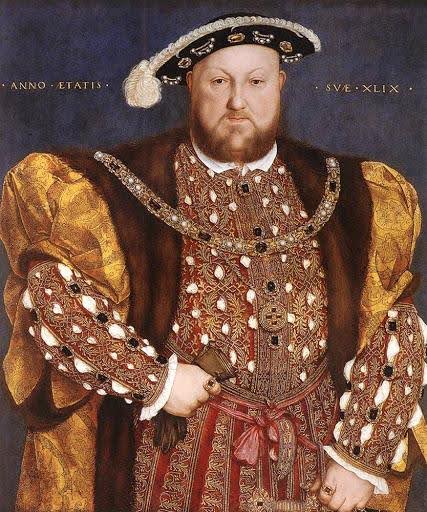

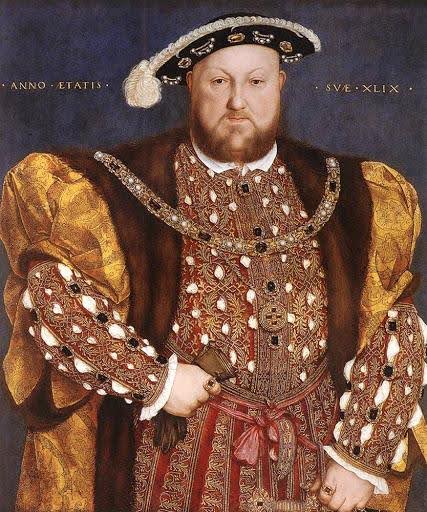

Henry VII favors long robes of fine cloth to show his wealth but his son, young Henry VIII, famed for his athletic, shapely legs, wears fitted hose and short robes so he can show off his best features. Now that the robe is so short, the flap that covers the join between the two separate legs of the hose [stockings] for modesty’s sake is now visible and Henry turns this into an asset by attaching a great codpiece to show off his virility. Since the courtiers take their fashion cues from the king, codpieces become a vital accessory. Henry is a well-muscled sporty young man but even so, his natural physique is accentuated by padding the shoulders of his doublet to extreme proportions.

Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet

Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet

In this image, you can see the slashes in the sleeves of his doublet so that little puffs of his fine shirt can be pulled through. The doublet has a skirt or peplum, of varying length according to fashion, underneath which are hidden ties (‘points’) or hooks, to attach the breeches.

The basics of men’s clothing is wearing layers. Next to your skin, you have a white linen shirt. This may be embroidered around the collar band. Katherine of Aragon introducebris ‘black-work’ embroidery from Spain and this becomes very fashionable, looking good on white linen. Later, the collar band is simply what your ruff is pinned onto, unless it has become a separate item by the time of your visit.

Breeches and hose come in a bewildering variety, going in and out of fashion almost weekly – another reason why a courtier’s wardrobe can empty his purse in no time, just trying to keep up. Here is a selection: round or French hose are short, full breeches ending anywhere between the upper thigh to just above the knee and excessively padded at the hips to accentuate your buttocks. These can make dancing or even walking elegantly quite difficult. Canions are tight-fitting tubes attached to the short version of the round hose to extend them to the knee. Below the knee, you wear stockings or ‘netherstocks’ held up with garters.

Whatever the style, the hose must be ‘paned’ – that is cut into narrow panels, joined at the waist and hem, with a colored lining showing between the panes. With so much padding and paning, you can understand why the codpiece is in decline, giving way to a modest buttoned or lace-up opening that doesn’t spoil the symmetry of your panes. Both your doublet and hose may also be decorated by ‘pinking’: slits cut in the fabric, in a pattern, with the coloured lining pulled through, as in Henry VIII’s time. One contemporary commentator of Elizabethan men’s fashion thought things had become quite ridiculous: ‘Except it were a dog in a doublet you shall not see any so disguised as are my countrymen of England’, he wrote and Elizabethan clothes indeed disguise the wearer’s true physique more than the fashions of any other period.

The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh

The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh

As you’ll see in the portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh [above], men also need to wear a bit of bling. Sir Walter has a single pearl earring, the sign of a truly fashionable man-about-town. Finger rings are a must.

Facial hair is also in vogue ever since Henry VIII grew a beard but at the Elizabethan court, the natural look isn’t enough. Once again, Sir Walter is a fine example to copy with his beard neatly trimmed to a point and his moustache curled. Set your ensemble with a short cape, fur-lined, and edged with a braid. This isn’t a practical cloak to keep you warm and dry but rather an accessory to be draped nonchalantly over one shoulder for that devil-may-care look that’s the height of fashion.

Footwear

No one of any significance goes without shoes. The pointy-toed, medieval styles go out of fashion almost as the first Tudor king sits on the throne. Rounded toes are the thing. But Henry VIII, maybe because he has broad feet, went further, creating a fashion for square toes. With more leather used to make the uppers, it’s also possible to have slashes to show off a contrasting inner lining, as with sleeves. However, these early Tudor styles are thin-soled and flat like their medieval predecessors but around 1500, somebody invents the ‘welt’ – a narrow strip of leather that goes around the shoe, in between the upper and the sole, making the shoe far more sturdy and able to withstand fancier shaping and decoration.

King Henry is tall and impressive anyway but others who want to emulate him could do with a few extra inches in height and by the time of Elizabeth heeled shoes have been invented. At first, the heel is just a wedge of cork or wood fixed between the leather sole and the upper but soon these become proper heels and part of the sole. With so much innovation in the world of shoemaking, in 1579 the queen grants their coat-of-arms to the Guild of Cordwainers in London.

Women’s dainty dress shoes, called ‘pinsons’, now with heels and a more dainty tapered toe, can be of silk, velvet, or brocade often with bejeweled rosettes. Mid-century, most are slip-ons but lacing and buckles become increasingly fashionable. A pair of Tudor or Elizabethan shoes are made the same for both feet so there is no correct right or left shoe so they can be swapped over for more even wear.

For outdoor wear, you can either put overshoes on to protect your indoor footwear, or you can have leather boots for walking and riding. Loose or tight-fitting, ‘gamaches’ are thigh-length high boots, and ‘buskins’ come to the calf.

Acts of Apparel

Acts of Apparel

In Henry VIII’s reign, realizing some of the up-and-coming wealthier gentry and merchants were wearing more sumptuous clothes than noblemen and courtiers, new laws are passed, termed Acts of Apparel, in 1509-10, 1514, 1515, and 1533. Europe has similar ideas but whereas their regulations tend to be drawn up by and apply only to individual towns, England’s laws come from Parliament and apply throughout the country, in theory, anyway.

According to the 1509-10 Act against Wearing of Costly Apparel, only the king, the queen, the king’s mother (the act must have been first drawn up before Margaret Beaufort died in June 1509), along with the king’s brothers and sisters can wear cloth of purple silk or gold, while dukes and marquises can only use cloth of gold as linings of their coats and doublets. An earl and those of higher rank may wear sable fur, but those below may not. Certain imported furs can be worn by royal grooms and pages, university graduates, yeomen, and landowners whose estates bring in an income of at least £11 per annum. Barons and knights of the Order of the Garter (the highest-ranking knights) are permitted to wear woolen textiles manufactured abroad but, for those of lesser status, it’s a crime to wear imported cloth. The same applies to wearing clothes dyed with the most expensive crimson and blue dyes.

Too much crimson dye?

Too much crimson dye?

Anyone who isn’t a lord’s son, a government servant, or a gentleman with an income from the land of at least £100 per annum is forbidden to wear velvet, satin, or damask, although, if their land is worth £20 or more, satin, damask or camlet may be used to line or trim their clothing but not for the main, visible body of the garment.

The problem is, as it has been for centuries, more and more successful merchants are becoming richer than the aristocracy. Intermarriage makes matters even more complex. The nobility want to share in mercantile wealth and merchants yearn for titles and high status. The solution is for a lord’s penniless second and untitled son to wed the daughter of a rich merchant but where do their offspring stand on the social ladder? The children aren’t the sons and daughters of a lord and yet they can now afford to live in greater opulence than their paternal relatives who still have titles. No wonder the laws are flouted.

An additional oddity concerns the way wealth is judged. Annual income from land is always regarded as having greater status than the same monetary income gained from trade. The sumptuary laws passed in the reign of King Edward III, in 1363, equated a landowner worth £200 a year to a merchant worth £1,000. These relative values are still maintained throughout the Tudor period. And there is another problem that becomes more acute in Henry VIII’s reign: that of people – and courtiers were some of the worst offenders – vying with their peers to be the most fashionable and expensively dressed and running up huge debts in the process. This situation leads to An Acte for Reformacyon of Excesse in Apparayle being passed in 1533:

…for the necessaire repressing avoiding and expelling of the inordinate excesse dailye more and more used in the sumptuous and costly araye and apparel accustomablye worne in this Realme, whereof hath ensued and dailie do chaunce suche sundrie high and notable inconveniences as to be the greate manifest an notorious detriment of the common Weale, the subvercion of good and politike order in knowledge and distinction of people according to their estates p[re]emyences dignities and degrees, and to the utter impoverysshement and undoyng of many inexpert and light persones inclined to pride moder of all vices…

Despite the declaration that these laws are intended to avoid the ‘notorious detriment of the common weal’, i.e. everyone, the legislation is aimed, as usual, at morally ‘light persons inclined to pride (mother of all vices)’. The laws also reiterate earlier attempts to mark out prostitutes from respectable women but in 1533 the earlier, medieval customs of what was considered respectable attire are enshrined in law for the first time, in particular, that a married woman must cover her hair – a ‘loose’ woman, i.e. one wearing her hair loose and uncovered is of easy virtue and up to no good.

An excess of wool production led to an Act of Parliament in 1571, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, to boost the sales of English woolen cloth. It becomes law that on Sundays and every official holiday all males over six years of age, except for the nobility and persons of degree, are to wear woolen caps on pain of a fine of three farthings (¾ of a penny) per day. Whether it works or not in practice, the act is repealed in 1597. In June 1574, Elizabeth issues the following statute from Greenwich Palace:

The excess of apparel and the superfluity of unnecessary foreign wares thereto belonging… is grown to such an extremity that the decay of the whole realm is like to follow (by bringing into the realm such superfluities of silks, cloth of gold, silver, and other vain devices of so great cost as of necessity the moneys of the realm is yearly conveyed out of the same to answer the said excess) but also the undoing of a great number of young gentlemen seeking by show of apparel to be esteemed as gentlemen not only consume themselves, their goods, and lands which their parents left unto them, but also run into such debts as they cannot live out of danger of laws without attempting unlawful acts… [edited]

Despite the fact that the queen and everyone else understand the cost of trying to keep up with the latest fashions, no amount of law-making can prevent the young gallants from spending far beyond their means.

Another 1597 proclamation on the subject goes into minute detail. Only earls can wear cloth of gold or purple silk. No one under the degree of knight is allowed silk ‘netherstocks’ (long stockings) or velvet outer garments. A knight’s eldest son may wear velvet doublets and hose but his younger brothers can’t. A baron’s eldest son’s wife may wear gold or silver lace which is forbidden to women below her in the pecking order. Who is allowed to wear what is supposed to be strictly controlled as the queen’s subjects must know their place and dress accordingly so that no one can be misled. At least, that’s the theory but you can see that the laws are confusing and is it any wonder that people ignore them? Will you obey the law or wear fashionable clothes, no matter the cost?

The frequency of acts and the huge number of laws passed proves that the authorities are losing the fight to keep the social distinctions, maintain morals and ethics, preserve the English economy against foreign imports, and restrain the excesses of fashion. However, a good many of the various sumptuary laws, dating back to as early as the fourteenth century, were still on the English statute books as recently as the 1800s, and, who knows, some may as yet remain, hidden in the dusty archives in the twenty-first century.

So this is an introduction of what to wear – or not – for the stylish courtier in the sixteenth century. If you wish to read about many interesting characters, places, food, and pastimes of the sixteenth century, my new book How to Survive in Tudor England will be published on 30th October 2023.

Blurb

Imagine you were transported back in time to Tudor England and had to start a new life there, without smartphones, internet, or social media. When transport means walking or, if you’re lucky, horseback, how will you know where you are or where to go? Where will you live and where will you work? What will you eat and what shall you wear? And who can you turn to if you fall ill or are mugged in the street, or God forbid if you upset the king? In a period when execution by beheading was the fate of thousands how can you keep your head in Tudor England?

All these questions and many more are answered in this new guidebook for time-travelers: How to Survive in Tudor England. A handy self-help guide with tips and suggestions to make your visit to the 16th century much more fun, this lively and engaging book will help the reader deal with the new experiences they may encounter and the problems that might occur.

Enjoy interviews with the celebrities of the day, and learn some new words to set the mood for your time-traveling adventure. Have an exciting visit but be sure to keep this book to hand.

Toni Mount Biography

Toni Mount Biography

Toni Mount researches, teaches, and writes about history. She is the author of several popular historical non-fiction books and writes regularly for various history magazines. As well as her weekly classes, Toni has created online courses for http://www.MedievalCourses.com and is the author of the popular Sebastian Foxley series of medieval murder mysteries. She’s a member of the Richard III Society’s Research Committee, a costumed interpreter, and speaks often to groups and societies on a range of historical subjects. Toni has a Master’s Degree in Medieval Medicine, Diplomas in Literature, Creative Writing, European Humanities, and a PGCE. She lives in Kent, England with her husband.

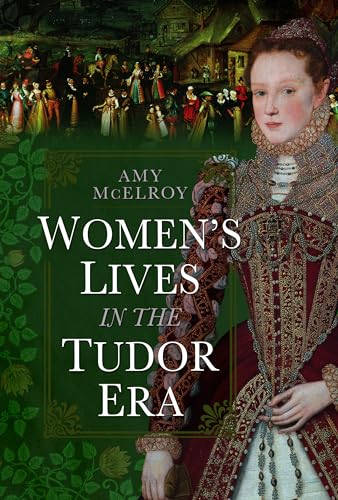

When we think about the Tudor dynasty, we often think about the famous men and women who defined the era. An era full of change in all aspects of life, from religious and political, to the arts and literature. Throughout these changes, we tend to focus on how they affected the lives of Tudor men, but there is a growing field of interest in the lives of the average Tudor women and how their lives were affected. In her latest book, “Women’s Lives in the Tudor Era,” Amy McElroy explores women’s life stages in 16th-century England and how their roles changed.

When we think about the Tudor dynasty, we often think about the famous men and women who defined the era. An era full of change in all aspects of life, from religious and political, to the arts and literature. Throughout these changes, we tend to focus on how they affected the lives of Tudor men, but there is a growing field of interest in the lives of the average Tudor women and how their lives were affected. In her latest book, “Women’s Lives in the Tudor Era,” Amy McElroy explores women’s life stages in 16th-century England and how their roles changed.

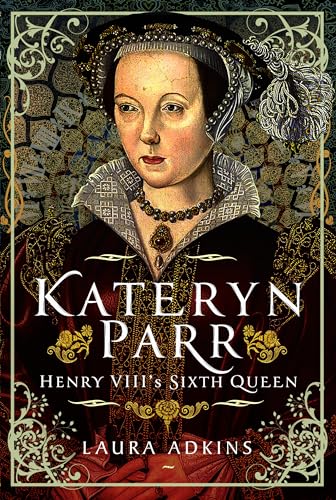

The final wife, the one who survived. These words are what people think about when it comes to Katherine (Kateryn) Parr. However, before she even met Henry VIII, she had already lived quite a life, being married twice before meeting the king. She was a scholar, reformer, daughter, stepmother, wife, and mother. A woman who lived a rather intriguing life and happened to marry the King of England, Kateryn Parr’s life has been told in numerous mediums for centuries. Now, Laura Adkins has chosen to write about this famous Tudor wife in the biography, “Kateryn Parr: Henry VIII’s Sixth Wife.”

The final wife, the one who survived. These words are what people think about when it comes to Katherine (Kateryn) Parr. However, before she even met Henry VIII, she had already lived quite a life, being married twice before meeting the king. She was a scholar, reformer, daughter, stepmother, wife, and mother. A woman who lived a rather intriguing life and happened to marry the King of England, Kateryn Parr’s life has been told in numerous mediums for centuries. Now, Laura Adkins has chosen to write about this famous Tudor wife in the biography, “Kateryn Parr: Henry VIII’s Sixth Wife.” When we think about England, we often think about a unified country with an illustrious history of wars and triumphs. However, England in the 10th century was drastically different. It was barely a country as it was newly formed through politics, but it faced the risk of elimination with a carousel of kings and Viking raiders. Some of the most notable kings of this era include Alfred, Edward the Elder, Athelstan, Edward the Martyr, and Aethelred II, but the most fascinating figures of this time were the women who were hidden in the shadows of the past. M.J. Porter uses the written record from the 10th and 11th centuries to tell the tales of these remarkable women in her book, “The Royal Women Who Made England: The Tenth Century in Saxon England.”

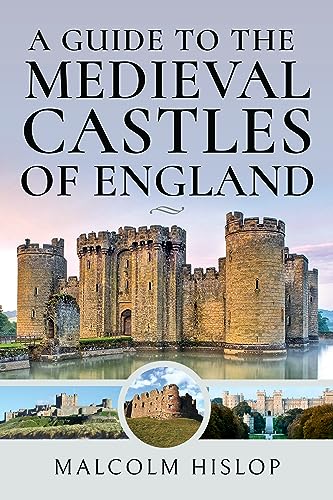

When we think about England, we often think about a unified country with an illustrious history of wars and triumphs. However, England in the 10th century was drastically different. It was barely a country as it was newly formed through politics, but it faced the risk of elimination with a carousel of kings and Viking raiders. Some of the most notable kings of this era include Alfred, Edward the Elder, Athelstan, Edward the Martyr, and Aethelred II, but the most fascinating figures of this time were the women who were hidden in the shadows of the past. M.J. Porter uses the written record from the 10th and 11th centuries to tell the tales of these remarkable women in her book, “The Royal Women Who Made England: The Tenth Century in Saxon England.” Castles, the monuments of medieval times, are buildings that hold many tales. Tales of sieges and sorrow, triumphs and tribulations. Through the centuries, their stones and foundations held many secrets. Some of the stories are famous, but most are hidden in the shadows of time and are hidden in ruins. Although castles exist in numerous countries and are centuries old, the castles of medieval England tell a story of a country facing turmoil and changing European and world history forever. Malcolm Hislop, a historian and researcher who specializes in architecture and archaeology, has written a single book exploring every medieval castle and its original architecture entitled, “A Guide to the Medieval Castles of England.”

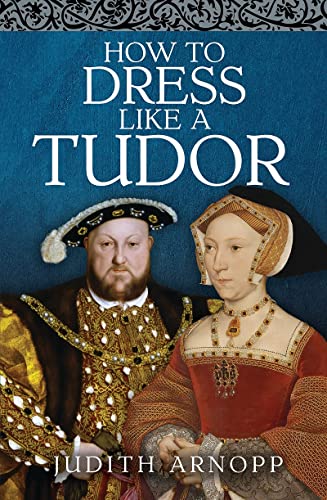

Castles, the monuments of medieval times, are buildings that hold many tales. Tales of sieges and sorrow, triumphs and tribulations. Through the centuries, their stones and foundations held many secrets. Some of the stories are famous, but most are hidden in the shadows of time and are hidden in ruins. Although castles exist in numerous countries and are centuries old, the castles of medieval England tell a story of a country facing turmoil and changing European and world history forever. Malcolm Hislop, a historian and researcher who specializes in architecture and archaeology, has written a single book exploring every medieval castle and its original architecture entitled, “A Guide to the Medieval Castles of England.” I am pleased to welcome Judith Arnopp to my blog today to share a blurb for her latest book, “How to Dress Like a Tudor.” I would like to thank Pen and Sword Books, The Coffee Pot Book Club, and Judith Arnopp for allowing me to be part of this blog tour.

I am pleased to welcome Judith Arnopp to my blog today to share a blurb for her latest book, “How to Dress Like a Tudor.” I would like to thank Pen and Sword Books, The Coffee Pot Book Club, and Judith Arnopp for allowing me to be part of this blog tour.  Blurb:

Blurb: Author Bio:

Author Bio: Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet

Henry VIII wearing a padded doublet  The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh

The fashionable Sir Walter Raleigh Acts of Apparel

Acts of Apparel  Too much crimson dye?

Too much crimson dye?

Toni Mount Biography

Toni Mount Biography Illegitimate royal children have been known to make an impact on history. Take Henry Fitzroy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, and Bessie Blount, whom Henry VIII acknowledged as his son. There were discussions about Henry Fitzroy becoming the heir apparent if Henry VIII did not have a legitimate son. But what about the illegitimate children that a king did not acknowledge? What might their lives have been like? The story of Mary Boleyn and her affair with King Henry VIII has been told many times, but the story of her daughter born during that time is lesser known. In her first full-length nonfiction book, “Henry VIII’s True Daughter: Catherine Carey, A Tudor Life,” Wendy J Dunn has taken on the task of discovering the truth of Catherine Carey’s parentage and how it impacted her life.

Illegitimate royal children have been known to make an impact on history. Take Henry Fitzroy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, and Bessie Blount, whom Henry VIII acknowledged as his son. There were discussions about Henry Fitzroy becoming the heir apparent if Henry VIII did not have a legitimate son. But what about the illegitimate children that a king did not acknowledge? What might their lives have been like? The story of Mary Boleyn and her affair with King Henry VIII has been told many times, but the story of her daughter born during that time is lesser known. In her first full-length nonfiction book, “Henry VIII’s True Daughter: Catherine Carey, A Tudor Life,” Wendy J Dunn has taken on the task of discovering the truth of Catherine Carey’s parentage and how it impacted her life. Time travel is a dream for history and science fiction nerds alike. To be able to go to a different period in history to witness major events sounds like it would be tons of fun, but it can also be treacherous if you do not know the era well. What should you wear? Where would you live? What would your occupation be and what should you eat? If you are invited to court, how do you navigate the crazy court intrigue and the ever-changing religious dilemma? Toni Mount has created the ideal book for those who wish to travel to the 16th century called, “How to Survive in Tudor England.”

Time travel is a dream for history and science fiction nerds alike. To be able to go to a different period in history to witness major events sounds like it would be tons of fun, but it can also be treacherous if you do not know the era well. What should you wear? Where would you live? What would your occupation be and what should you eat? If you are invited to court, how do you navigate the crazy court intrigue and the ever-changing religious dilemma? Toni Mount has created the ideal book for those who wish to travel to the 16th century called, “How to Survive in Tudor England.” Rulers cannot govern alone. They require a team of men and women behind them to operate as a cohesive unit. The same can be said for rulers during the Tudor dynasty. We know the stories of men like Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell, two men who rose through the ranks to prominent seats of power to ultimately have disastrous falls from grace. However, there was a third Tudor politician who should be in this discussion about rags-to-riches stories. He was the son of a common merchant who went to serve most of the Tudor monarchs as an advisor. Conspiracies and rebellions kept him on his toes, but he ultimately survived the Tudor dynasty, which was a difficult thing to achieve. His name was Lord William Paget and his story is told by his descendant Alex Anglesey in his debut book, “The Great Survivor of the Tudor Age: The Life and Times of Lord William Paget.”

Rulers cannot govern alone. They require a team of men and women behind them to operate as a cohesive unit. The same can be said for rulers during the Tudor dynasty. We know the stories of men like Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell, two men who rose through the ranks to prominent seats of power to ultimately have disastrous falls from grace. However, there was a third Tudor politician who should be in this discussion about rags-to-riches stories. He was the son of a common merchant who went to serve most of the Tudor monarchs as an advisor. Conspiracies and rebellions kept him on his toes, but he ultimately survived the Tudor dynasty, which was a difficult thing to achieve. His name was Lord William Paget and his story is told by his descendant Alex Anglesey in his debut book, “The Great Survivor of the Tudor Age: The Life and Times of Lord William Paget.” Have you ever watched a historical drama and wondered what it might have been like to wear the outfits for that period? You see so many reenactment groups online and you are envious of their talents for being able to bring clothing from the past, especially clothes from the 16th century, to life in the modern age. What might it have been like to dress like a lord or a lady? What about a commoner or a monk? How did fashion change throughout the Tudor dynasty? Judith Arnopp answers all of these questions and more in her latest book, “How to Dress Like a Tudor.”

Have you ever watched a historical drama and wondered what it might have been like to wear the outfits for that period? You see so many reenactment groups online and you are envious of their talents for being able to bring clothing from the past, especially clothes from the 16th century, to life in the modern age. What might it have been like to dress like a lord or a lady? What about a commoner or a monk? How did fashion change throughout the Tudor dynasty? Judith Arnopp answers all of these questions and more in her latest book, “How to Dress Like a Tudor.”