Today, I am pleased to welcome Carol McGrath to the blog to discuss Tudor hygiene as part of the Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England blog tour. I would like to thank Carol McGrath and Pen and Sword Books for allowing me to be part of this tour.

Today, I am pleased to welcome Carol McGrath to the blog to discuss Tudor hygiene as part of the Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England blog tour. I would like to thank Carol McGrath and Pen and Sword Books for allowing me to be part of this tour.

Did Tudors smell whiffy? Did they care about personal hygiene? It may surprise you that the Tudors cared about cleanliness despite the fact many did not bathe regularly. Henry VIII frequently took baths and had a new bathhouse constructed at Hampton Court for his personal use and a steam bath at Richmond Palace. This new bath was made of wood but lined with a linen sheet to protect his posterior from catching splinters. It was a marvellous feat of Tudor engineering and allowed water to flow into it from a tap fed by a lead pipe bringing water from a spring over three miles distant from the palace. Tudor engineers were clever enough to pass the pipe underneath the Thames river bed using gravity to create strong water pressure to spurt up two floors into the royal bathroom.

It was important to most Tudors not to stink and particularly important not to smell unpleasant when contemplating relations with a lover. Stinking like a beast was totally unacceptable to a Tudor because, ideally, humans should smell sweet. Of course, the Tudor world was less sanitized than our world. Even so, people were not unaware of bad smells around them, and they actually feared nasty pongs. Medicine taught that disease spread through miasma or foul-smelling airs. Importantly, Tudors also believed that sweet smells could be a key indicator of a person’s moral state, never mind that smelling sweet could help attract a lover.

Bathing for most Tudors meant a dip in the river. For those dwelling in towns, bathing facilities such as bathhouses existed during the first few decades of the era. Crusaders had brought the habit of bathing back from the East, thereby making the idea of bathhouses popular.

Bathing for most Tudors meant a dip in the river. For those dwelling in towns, bathing facilities such as bathhouses existed during the first few decades of the era. Crusaders had brought the habit of bathing back from the East, thereby making the idea of bathhouses popular.

Hygiene meant both cleaning oneself and one’s clothes regularly. Just as the Church clamped down on sexual freedoms, it had opinions on bathing: heat could inflame the senses, and washing nude was a sign of vanity, even sexual corruption, so they often wore shirts while bathing. You could scent a bath with flowers and sweet green herbs to help cure ailments, therefore attaching a medicinal element to the practice. Exotic perfumes such as civet and musk were used in soaps, as well as rose water, violet, lavender, and camphor. For those who could afford scented soaps, they certainly were available.

Where public bathhouses went, sex soon followed, so it is no wonder the ever-critical Church complained. Tudor brothels were called ‘stews’ and ‘to lather up’ was an early sixteenth-century slang phrase for ejaculation which came from the notion that one could stew in hot water and steam within a bathhouse. As recently as the previous century, the City of London officially recognized the borough of Southwark as having the highest concentration of bathhouses in London. Ironically, this was an area owned by the Bishop of Winchester, and since many bathhouses were also brothels, their sex workers acquired the alternative name of Winchester Geese.

As the sixteenth century continued, bathing fell into decline as new medical advice suggested it weakened the body. Cleaning the skin left it open to infection. This was considered an outside agency that drifted in the air like spores and which rose from places of putrefaction. The skin’s pores were one body area through which these nasty spores could enter, so medical advice determined that the skin needed to be preserved as a barrier. Pores were a secondary route into the body, and the filth produced by the body must be removed completely and quickly to avoid reabsorption. It became important to wash your shirt and change it frequently to keep clean.

Linen shirts, smocks, under-breeches, hose, collars, coifs, and skull caps allowed the total body coverage. As a fabric, linen was very absorbent. It drew sweat and grease from the skin into the weave of the cloth. Since linen acted like a sponge, the Tudors thought it would draw out waste products from the body and improve the body’s circulation, strengthen the constitution and even restore the balance of the humours.

Laundresses were popular during Tudor times, not just to keep linen washed but because the washerwomen were easily connected with sex. They were badly paid, so sex work was a way to subsidize their income in many cases. Washerwomen sometimes became known as ‘lavenders.’ The word lavender comes from the Latin lavare to wash, and the word to launder derives from these sweet-smelling flowers. Lavender grows all over Europe, and as it was cheap and readily available, it was used widely when washing clothing. The sixteenth-century poem Ship of Fools contains the following lines:

Thou shalt be my lavender Laundress.

To Wash and keep all my gear

Our two beds together shall be set

Without any let.

People used linen to scrub the body. The Tudor Gentleman, Sir Thomas Elyot, wrote a book in 1534 called The Castel of Health. He suggests an early morning hygiene regime to ‘rubbe the body with a course lynnen clothe, first softly and easilye, and after that increase more and more, to a hard and swift rubbynge, untyll the flesh do swelle and to be somewhat ruddy and that not only down ryghte, but also overthrart and round.’ Rubbing vigorously after exercise could draw the body’s toxins out through open pores, and the rough linen cloth would carry them away. Most people only owned two or three sets of underwear. Listed underwear occasionally turned up in Tudor inventories, and linens would often be recorded in wills as bequeathed to others.

Ruth Goodman, a well-known social historian, once followed a Tudor body cleansing regime for a period of three months while living in modern society. No one complained or even noticed a sweaty smell. She wore natural fibre on top of the linen underwear but took neither a shower nor a bath for the whole period. When she recorded The Monastery Farm for television, she only changed her linen smock once weekly and her hose three times over six months, and she still did not pong. Tudor England was not a place where everyone smelled as sweetly as most people who shower daily today, but its people generally managed not to stink. Of course, the past did smell differently. Even so, being clean and sweet-smelling did matter to many Tudors.

Carol McGrath

Carol McGrath

Following a first degree in English and History, Carol McGrath completed an MA in Creative Writing from The Seamus Heaney Centre, Queens University Belfast, followed by an MPhil in English from the University of London. The Handfasted Wife, the first in a trilogy about the royal women of 1066, was shortlisted for the RoNAS in 2014. The Swan-Daughter and The Betrothed Sister complete this highly acclaimed trilogy. Mistress Cromwell, a best-selling historical novel about Elizabeth Cromwell, wife of Henry VIII’s statesman, Thomas Cromwell, republished by Headline in 2020. The Silken Rose, first in a Medieval She-Wolf Queens Trilogy featuring Ailenor of Provence, was published in April 2020 by the Headline Group. This was followed by The Damask Rose. The Stone Rose will be published in April 2022. Carol writes Historical non-fiction as well as fiction. Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England will be published in February 2022. Find Carol on her website:

Follow her on amazon @CarolMcGrath

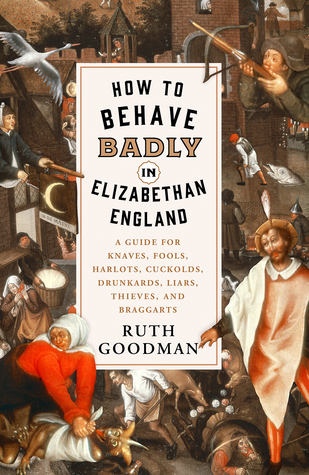

In many books about the different mannerisms and routines of different dynasties, we tend to see how the average person lived in the most prim and proper manner. How they avoided trouble at all costs to provide the best life that they could for their families. Yet, we know that there were those who did not adhere to the rules. They chose to rebel against the natural way of life. Every social echelon had their own rule-breakers, but what were these rules that they chose to break? How are these troublemakers of the past similar and different from our modern-day rebels? Famed experimental archeologist and historian Ruth Goodman takes her readers on a journey through the Elizabethan and the early Stuart eras to show how the drunkards, thieves, and knaves made a name for themselves. The name of this rather imaginative book is “How to Behave Badly in Elizabethan England: A Guide for Knaves, Fools, Harlots, Cuckolds, Drunkards, Liars, Thieves, and Braggarts”.

In many books about the different mannerisms and routines of different dynasties, we tend to see how the average person lived in the most prim and proper manner. How they avoided trouble at all costs to provide the best life that they could for their families. Yet, we know that there were those who did not adhere to the rules. They chose to rebel against the natural way of life. Every social echelon had their own rule-breakers, but what were these rules that they chose to break? How are these troublemakers of the past similar and different from our modern-day rebels? Famed experimental archeologist and historian Ruth Goodman takes her readers on a journey through the Elizabethan and the early Stuart eras to show how the drunkards, thieves, and knaves made a name for themselves. The name of this rather imaginative book is “How to Behave Badly in Elizabethan England: A Guide for Knaves, Fools, Harlots, Cuckolds, Drunkards, Liars, Thieves, and Braggarts”. The Tudor era has enchanted generations of history lovers with its interesting monarchs and scandals. The beautiful outfits, the political drama of the age, the legendary marriages of King Henry VIII, the children of Henry VIII, and how England grew into a dominant force in European politics. These are the things that people tend to focus on when studying the Tudors, yet this is a very narrow view of the time period. We tend to focus on the inner workings of the court system, but we don’t focus on the common people who lived in England during this time. What was it like to live in Tudor England for the common people? This is the question that Ruth Goodman explores in her book, “How To Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life”.

The Tudor era has enchanted generations of history lovers with its interesting monarchs and scandals. The beautiful outfits, the political drama of the age, the legendary marriages of King Henry VIII, the children of Henry VIII, and how England grew into a dominant force in European politics. These are the things that people tend to focus on when studying the Tudors, yet this is a very narrow view of the time period. We tend to focus on the inner workings of the court system, but we don’t focus on the common people who lived in England during this time. What was it like to live in Tudor England for the common people? This is the question that Ruth Goodman explores in her book, “How To Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life”.