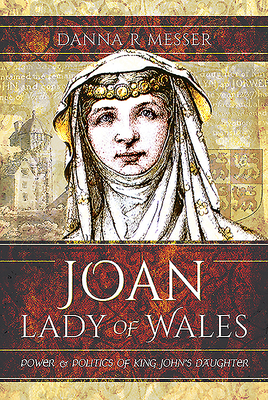

Medieval women held many different titles that defined their roles and their connections. Mothers, daughters, and wives tended to be the most popular and the most common. Titles such as queen, political diplomat, and peace weaver tend to be rare and given to women of power. Yet, these words accurately depict a unique woman who lived during the Angevin/ Plantagenet dynasty. She was the illegitimate daughter of the notorious King John and the wife of Llywelyn the Great, a Prince of Wales. She worked tirelessly to establish peace between England and Wales, yet she has not received much attention in the past. Her name was Joan, Lady of Wales, and her story is brought to life in Danna R. Messer’s book, “Joan, Lady of Wales: Power and Politics of King John’s Daughter”.

Medieval women held many different titles that defined their roles and their connections. Mothers, daughters, and wives tended to be the most popular and the most common. Titles such as queen, political diplomat, and peace weaver tend to be rare and given to women of power. Yet, these words accurately depict a unique woman who lived during the Angevin/ Plantagenet dynasty. She was the illegitimate daughter of the notorious King John and the wife of Llywelyn the Great, a Prince of Wales. She worked tirelessly to establish peace between England and Wales, yet she has not received much attention in the past. Her name was Joan, Lady of Wales, and her story is brought to life in Danna R. Messer’s book, “Joan, Lady of Wales: Power and Politics of King John’s Daughter”.

I would like to thank Pen and Sword Books and Net Galley for sending me a copy of this book. I did not know much about Joan, except what I read about her in Sharon Bennett Connolly’s latest book, “Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth-Century England”. She sounded really interesting so when I heard about this book by Messer, I wanted to read it to learn more about Joan.

As someone who did not know a lot about Joan or medieval Wales, I found this book informative and enjoyable. Messer takes the time to explain what life was like for a royal Welsh couple, like Joan and Llywelyn, and why their marriage made such an impact in the long run. On paper, it was a princess from England marrying a prince from Wales, but what made this union so unique was the fact that Joan was the illegitimate daughter of King John and yet she was treated like a beloved legitimate child. Of course, this marriage was first and foremost, a political match, but it seemed to have developed into a strong and loving partnership, that endured 30 years of trials and tribulations.

One of the major trials that Joan had to deal with was to prevent England and Wales from going to war against each other. Truly a monumental challenge for, as Messer meticulously points out, Llywelyn and either King John or King Henry III were constantly having disagreements. I could just picture Joan getting exasperated that she had to try to calm things down between England and Wales every single time. Her diplomatic skills were truly remarkable, especially with how much influence she possessed in both countries.

Probably the most controversial event in Joan’s life is her affair with William de Braose, which led to his execution and her imprisonment. Messer does a good job explaining what we know about this situation. Unfortunately, like many events in Joan’s life, Messer has to use a bit of guesswork to try and put together the clues about Joan and figure out what happened. It can be a bit frustrating, but we have to remember that Joan lived over 800 years ago and women were not recorded as detailed as they are now or even 500 years ago. I think we can give Messer a pass on guessing where Joan was and what her role was in certain events.

Overall, I found this book enlightening. I think Messer’s writing style is engaging and she was dedicated to finding out the truth, as far as the facts would take her. I think this is a fantastic book for someone who needs an introduction to medieval Welsh royal lifestyle, the power of royal Welsh women, and of course, a meticulously detailed account of the life of Joan, Lady of Wales. If this describes you, check out “Joan, Lady of Wales: Power and Politics of King John’s Daughter” by Danna R. Messer.

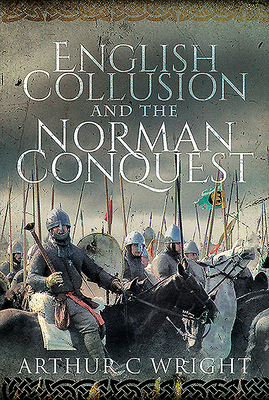

The Norman Conquest of 1066 was one of the most important dates in English and world history. It signaled the start of the Norman influence in England with Duke William, also known as William the Conqueror, becoming King of England. But does William I deserve the reputation that is attributed to him in history, or should we be careful with how we view him because his story is told by the avaricious Church? How much help did William and the Normans receive from their English counterparts? Can we call this event a “conquest”? Who was to blame for the “Harrowing of the North”? These questions and more are discussed in Arthur C. Wright’s latest book, “English Collusion and the Norman Conquest”.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 was one of the most important dates in English and world history. It signaled the start of the Norman influence in England with Duke William, also known as William the Conqueror, becoming King of England. But does William I deserve the reputation that is attributed to him in history, or should we be careful with how we view him because his story is told by the avaricious Church? How much help did William and the Normans receive from their English counterparts? Can we call this event a “conquest”? Who was to blame for the “Harrowing of the North”? These questions and more are discussed in Arthur C. Wright’s latest book, “English Collusion and the Norman Conquest”. When one thinks about Medieval Europe and buildings, we tend to focus on the luxurious castles with their impenetrable walls. It is a rather glamorous image, but the problem is it is not accurate. Castles were used for defensive measures to protect the kingdom from attacks, either from outsiders or, in some cases, from within. Medieval warfare and castles go hand in hand, but one conflict where we tend to forget that castles play a significant role is in the civil war between the Yorks and the Lancasters, which we refer to today as The Wars of the Roses. Dr. Dan Spencer has scoured the resources that are available to find out the true role of these fortresses, both in England and in Wales, in this complex family drama that threw England into chaos. His research has been compiled in his latest book, “The Castle in the Wars of the Roses”.

When one thinks about Medieval Europe and buildings, we tend to focus on the luxurious castles with their impenetrable walls. It is a rather glamorous image, but the problem is it is not accurate. Castles were used for defensive measures to protect the kingdom from attacks, either from outsiders or, in some cases, from within. Medieval warfare and castles go hand in hand, but one conflict where we tend to forget that castles play a significant role is in the civil war between the Yorks and the Lancasters, which we refer to today as The Wars of the Roses. Dr. Dan Spencer has scoured the resources that are available to find out the true role of these fortresses, both in England and in Wales, in this complex family drama that threw England into chaos. His research has been compiled in his latest book, “The Castle in the Wars of the Roses”.

When we study history, we tend to focus on the lives of the elite and the royalty because their lives are well documented. However, there was a large majority of the population who tends to be forgotten in the annals of the past. They are the lower classes who were the backbone of society for centuries, the people who we would call peasants. Now, if we know so much about the higher echelons of society, we must ask ourselves what was life like for those who had almost nothing in life. How did they work? When they did speak out about injustices through revolutions, how were they received? How did they worship? How were they educated? How did they relax after long days of back-breaking labor? Where did they live? These questions and more are answered in Terry Deary’s latest book, “The Peasants’ Revolting Lives”.

When we study history, we tend to focus on the lives of the elite and the royalty because their lives are well documented. However, there was a large majority of the population who tends to be forgotten in the annals of the past. They are the lower classes who were the backbone of society for centuries, the people who we would call peasants. Now, if we know so much about the higher echelons of society, we must ask ourselves what was life like for those who had almost nothing in life. How did they work? When they did speak out about injustices through revolutions, how were they received? How did they worship? How were they educated? How did they relax after long days of back-breaking labor? Where did they live? These questions and more are answered in Terry Deary’s latest book, “The Peasants’ Revolting Lives”. The year of 1215 marked a turning point in English history with the sealing of a rather unique document; the Charter of Liberties, or as we know it today, the Magna Carta. It was a charter from the people to a king demanding the rights that they believed that they deserved. Those who sealed it were rebel barons who were tired of the way King John was running the country, yet instead of asking for his removal, they wanted reform. The clauses mostly concerned the problems of the men who made the charter, however, three clauses dealt with women specifically. In her latest book, “Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England”, Sharon Bennett Connolly explores the lives of the women who were directly impacted by this document.

The year of 1215 marked a turning point in English history with the sealing of a rather unique document; the Charter of Liberties, or as we know it today, the Magna Carta. It was a charter from the people to a king demanding the rights that they believed that they deserved. Those who sealed it were rebel barons who were tired of the way King John was running the country, yet instead of asking for his removal, they wanted reform. The clauses mostly concerned the problems of the men who made the charter, however, three clauses dealt with women specifically. In her latest book, “Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England”, Sharon Bennett Connolly explores the lives of the women who were directly impacted by this document. When one studies English history, many people tend to focus on the year 1066 with William the Conqueror and the Norman Conquest as a starting point. However, just like any great civilization, others formed the foundation of English history; they were known as the Anglo-Saxons. What we know about the Anglo-Saxons come from the records of the kings of the different kingdoms of England, which paints a picture of harsh and tumultuous times with power-struggles. However, every strong king and gentleman of the time knew that to succeed, they needed a woman that was equally strong with a bloodline that would make them untouchable. The stories of these women who helped define this era of Anglo-Saxon rulers in England have long been hidden, until now. In her latest book, “Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England”, Annie Whitehead dives deep into the archives to shed some light on the stories of the formidable women who defined an era.

When one studies English history, many people tend to focus on the year 1066 with William the Conqueror and the Norman Conquest as a starting point. However, just like any great civilization, others formed the foundation of English history; they were known as the Anglo-Saxons. What we know about the Anglo-Saxons come from the records of the kings of the different kingdoms of England, which paints a picture of harsh and tumultuous times with power-struggles. However, every strong king and gentleman of the time knew that to succeed, they needed a woman that was equally strong with a bloodline that would make them untouchable. The stories of these women who helped define this era of Anglo-Saxon rulers in England have long been hidden, until now. In her latest book, “Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England”, Annie Whitehead dives deep into the archives to shed some light on the stories of the formidable women who defined an era. The stories of the men behind the English crown can be as compelling as the men who wore the crown themselves. They were ruthless, cunning, power-hungry, and for many of them, did not last long. However, there were a select few who proved loyal to the crown and lived long and eventful lives. They are not as well known as their infamous counterparts, yet their stories are just as important to tell. One such man was the grandfather of two of Henry VIII’s wives and the great-grandfather of Elizabeth I. He lived through the reign of six kings and led his men to victory at the Battle of Flodden against King James IV of Scotland towards the end of his life. Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk had his fair shares of highs and lows, including imprisonment, but his story is rarely told. That is until now. Kirsten Claiden-Yardley has taken up the challenge to explore the life of this rather extraordinary man in her book, “The Man Behind the Tudors: Thomas Howards, 2nd Duke of Norfolk”.

The stories of the men behind the English crown can be as compelling as the men who wore the crown themselves. They were ruthless, cunning, power-hungry, and for many of them, did not last long. However, there were a select few who proved loyal to the crown and lived long and eventful lives. They are not as well known as their infamous counterparts, yet their stories are just as important to tell. One such man was the grandfather of two of Henry VIII’s wives and the great-grandfather of Elizabeth I. He lived through the reign of six kings and led his men to victory at the Battle of Flodden against King James IV of Scotland towards the end of his life. Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk had his fair shares of highs and lows, including imprisonment, but his story is rarely told. That is until now. Kirsten Claiden-Yardley has taken up the challenge to explore the life of this rather extraordinary man in her book, “The Man Behind the Tudors: Thomas Howards, 2nd Duke of Norfolk”. The romanticized conflict that was known as the Wars of the Roses had numerous colorful figures. From the sleeping king, Henry VI and his strong wife Margaret of Anjou to the cunning Kingmaker Warwick and the hotly debated figure Richard III, these men and women made this conflict rather fascinating. However, there was one man who would truly define this era in English history, Edward IV. He was a son of Richard duke of York who fought to avenge his father’s death and the man who would marry a woman, Elizabeth Woodville, who he loved instead of allying himself with a European power. These are elements of his story that most people know, but he was first and foremost an effective general, which is a side that is rarely explored when examining his life. David Santiuste decided to explore this vital part of Edward’s life in his book, “Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses”.

The romanticized conflict that was known as the Wars of the Roses had numerous colorful figures. From the sleeping king, Henry VI and his strong wife Margaret of Anjou to the cunning Kingmaker Warwick and the hotly debated figure Richard III, these men and women made this conflict rather fascinating. However, there was one man who would truly define this era in English history, Edward IV. He was a son of Richard duke of York who fought to avenge his father’s death and the man who would marry a woman, Elizabeth Woodville, who he loved instead of allying himself with a European power. These are elements of his story that most people know, but he was first and foremost an effective general, which is a side that is rarely explored when examining his life. David Santiuste decided to explore this vital part of Edward’s life in his book, “Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses”. In the medieval world, a person’s lineage was everything. It determined who you could marry, what job you could have, and where you could live. To be considered a legitimate child meant that the world was your oyster, for the most part. It was a bit difficult if you were considered an illegitimate child. We often look at lineage when it comes to royal families, but what about the nobility and the gentry. If you were considered an illegitimate child in the late medieval time period to a family who is part of the nobility or the gentry, what kind of opportunities would be available to you? This question and others are explored in Helen Matthews’ book, “The Legitimacy of Bastards: The Place of Illegitimate Children in Later Medieval England”.

In the medieval world, a person’s lineage was everything. It determined who you could marry, what job you could have, and where you could live. To be considered a legitimate child meant that the world was your oyster, for the most part. It was a bit difficult if you were considered an illegitimate child. We often look at lineage when it comes to royal families, but what about the nobility and the gentry. If you were considered an illegitimate child in the late medieval time period to a family who is part of the nobility or the gentry, what kind of opportunities would be available to you? This question and others are explored in Helen Matthews’ book, “The Legitimacy of Bastards: The Place of Illegitimate Children in Later Medieval England”.